Imagine a team where every member can execute every task with near-perfection results. Is it nice? Is it possible?

In this article I’ll discuss Cross-Functionality and a dysfunction I call Fake Cross-Functionality.

Self-Organization and Cross-Functionality in Agility

The Manifesto for Agile Software Development, with its principles, tells us about self-organization:

The best architectures, requirements, and designs emerge from self-organizing teams.

This means that, given goals, the team itself will find out what to do and how to do it.

This is only possible if the team has all the necessary expertise. This is what cross-functionality is about. Scrum defines it as:

Scrum Teams are cross-functional, meaning the members have all the skills necessary to create value each Sprint.

Pay attention that “the members have all the skills”, not "all the members have all the skills".

Fake Cross-Functionality

I sometimes hear that cross-functionality is every individual member of a team having all the necessary skills to create the product.

Mike Cohn has a word on that:

Perhaps the most prevalent and persistent myth in agile is that a cross-functional team is one on which each person possesses every skill necessary to complete the work.

This is simply not true.

A cross-functional team has members with a variety of skills, but that does not mean each member has all of the skills.

I think it is impossible for all team members have all skills. At least, it is impossible in a complex product development. Aiming for that is what I call Fake Cross-Functionality.

Fake Cross-Functionality is not about a team depending on external resources for missing skills. This completely misses the point of cross-functionality, so it does not make sense to call it “fake”.

I use the word “fake” in the sense of being cross-functionality in an unachievable state.

Defining it:

Fake Cross-Functionality: everyone is expected to have the ability to perform every function inside a team. The lack of space for specialization results in mediocre outputs and inadequate processes. The broad scope of work confuses people about their role inside the team. Demotivation takes place and worsens the previous aspects.

It is a pretty scary situation. I’ll tell you why.

Impossible

There’s no way a person can learn everything a team needs to do. That’s why we have specialists and generalists.

Generalists vs. Specialists

Not going into details of what a generalists/specialists are: the first group has some knowledge of various subjects, while the second has deep knowledge of a specific subject.

Of course, even specialists can be generalists in fewer topics. Also, generalists have varying levels of knowledge for each subject.

Knowledge is not something where 1+1=2, at the same time the quality of the outcomes in a specific aspect are limited by the depth of knowledge the team has of that aspect.

The quality of the outcomes in a specific aspect are limited by the depth of knowledge the team has of that aspect.

Imagine a critical product where security is a key factor. Having a team only of generalists will result in an insecure software.

Consider another team where everyone has basic knowledge about software testing. Probably, they’ll have issues in this regard.

If everyone can code, but no one studied software architecture, it won’t take long to things be a nasty mess.

In a team, specialists and generalists support each other to maintain the workflow and maximize value generation.

Cross-Functional Team Setup Examples

Here I’ll discuss some example setups for people working in a software development organization. The story starts with the teams working in a non-cross-functional setup and trying alternatives.

Of course, a real situation may not be exactly as described. They may mix parts of examples, and the proposed solutions may be different.

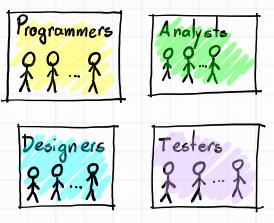

To give some context, the organization of the example has four main roles:

- Programmers: code new functionality, give maintenance to the code and write automated tests (unit and integration tests). Domain and functional knowledge vary, but everyone if proficient in programming best practices and the languages they work with.

- Business analysts: understand the market needs and create the requirements. High domain knowledge, with varying functional knowledge. A very small part of the analysts have technical knowledge such as programming.

- Testers: write automated tests (end to end tests) and perform manual exploratory tests. Good domain and functional knowledge. Good programming skills.

- Designers: Provide guidelines for the user interface and are responsible to maintain a good user experience across all the products. Domain and functional knowledge vary. Few people with basic programming skills.

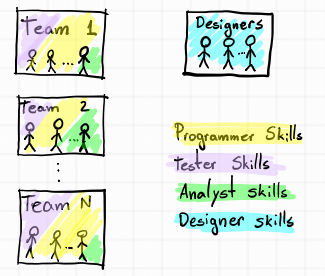

Bad Example #1: Group by Skills

Consider this organization groups people by their roles, as in the picture below.

Clearly this is not cross-functionality. The organization has all necessary skills, but they are in silos. This makes communication difficult, with lots of hand-overs preventing the creation of incremental deliveries that generate value constantly.

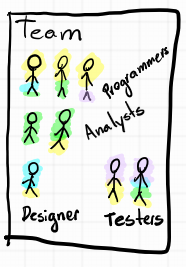

Good Example #1: Cross-Functional With Predefined Roles

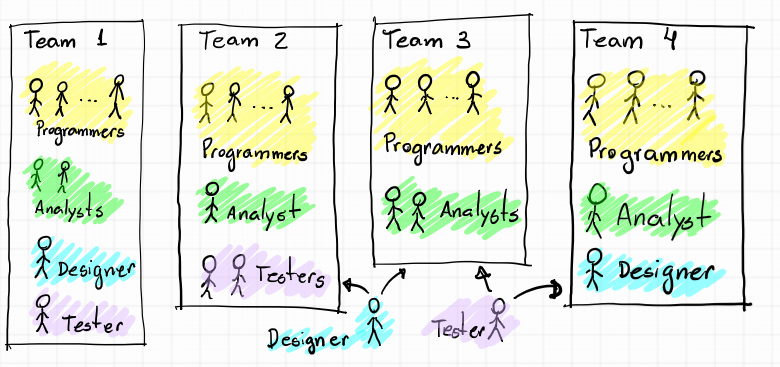

Given the context of the first example, a better way to set up those people is by grouping people with different skills. When all the skills in a team are summed up, the team has everything needed to develop software, as the following picture:

You can even have one person assigned to more than one team, if the amount of work for each of these teams isn’t that much.

The main idea behind a cross-functional team is create cohesion, so everyone works towards a common goal.

If the team doesn’t work as a cohesive unit, people may say “My role is X, so I’ll only do X”. The handovers mentioned in the previous example continue to exist, now internally to the team.

A solution may be to abolish roles inside the team. People may still have their expertise area, but they’ll be responsible for the team’s outcomes, not just “finishing their individual tasks”.

Good Example #2: Cross-Functional Without Predefined Roles

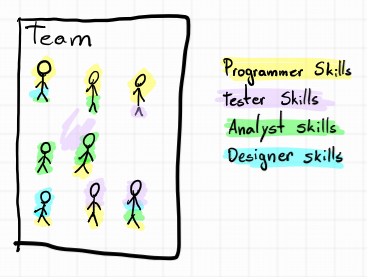

In this example, there are no roles and people need to have more than one skill set. And this is completely feasible: as previously stated, people in a role had skills “required” for another role, at varying levels. Consider the picture below:

There’s a “skill spectrum” based on the initial roles for each person. When everyone’s skills are summed up, the team has everything necessary to develop their product.

What can go wrong? The necessary skills may be silently absent.

Consider two people with designer skills leave the team. Even with a remaining person with designer skills, team’s needs are not fulfilled. The current design knowledge is very basic, and the team is not cross-functional anymore, as in the next picture:

If the skill set of the whole team is correctly managed, this won’t happen. But it can be quite hard to do so with informal roles or without them at all.

One poor way to manage these skill dependencies is trying to achieve Fake Cross-Functionality: to overcome the skill losses when someone leaves the team, everyone is expected to have all the skills necessary for the team. As we discussed previously, this is unfeasible.

Bad Example #2: Quasi-Cross-Functional Team With Dependencies

There are insufficient designer skills in the team. It is an issue across the other teams as well. Instead of putting the necessary skills into each team, management decides to create a separate team for designers, which will collaborate with all other teams like in the picture below:

This is not cross-functionality. Design skills are necessary and teams don’t have it. They rely on external resources to do their work.

When the teams are set up in a Quasi-Cross-Functional way, bogus solutions may arise. For example, defining someone inside the team as a “point of contact” or “responsible” for the missing skills. Just doing so does not solve the problem.

Good Example #3: Cross-Functional Acknowledging Generalists/Specialists

The Example of a Cross-Functional with Predefined Roles was the one which worked the best until now for the organization. It had the issue of people not being accountable for team’s goals, just minding their own work. This was not and issue in the example of Cross-Function Team Without Predefined Roles, but managing the skills proved to be difficult for this organization.

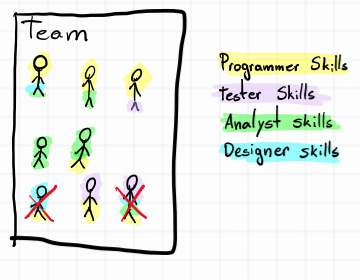

They decide to merge this two approaches, defining roles, mapping skills and acknowledging the existence of specialists/generalists, like in the picture below:

To make the example understandable, let’s use names. Bob has the official role of Tester, but he is a generalist. The team knows Bob can assist the Designer or be a temporary substitute. Bob has no knowledge in business analysis, and there’s no plan to improve that. Everyone agrees it is better for Bob to focus primarily in testing and design activities.

This is the way I think works the best because everyone is aware of their responsibilities, and it’s easier to manage skill dependencies because of transparency. It is a nice way to give opportunity for people to work in something different (curiosity, learning etc.), also increasing focus on team’s goals instead of people just trying to finish their tasks.

Conclusion

Agility is not about creating silver bullets. The best setup for your cross-functional teams depends on your organization’s reality. The only “dogma” you may follow is that cross-functional teams have all the necessary skills to develop whatever they develop. And remember: Cross-functional teams have all skills. Individual team members may (almost certainly) not have all the necessary skills at the necessary level.

Some advice for setting up cross-functional teams:

-

Define clear goals. Without them, you can’t define the correct skill set for the team.

-

List the necessary skills and how much you need of each. The list may not be the same for all teams in the same organization. It also changes over time.

-

Acknowledge generalists. They can find a way to solve almost any problem, also providing diversity for any discussion. Their existence is what creates the opportunity for specialists to exist.

-

Remember generalists don’t have knowledge on everything. Different people have different skill sets.

-

Acknowledge specialists. They are responsible to take quality to the next level in specific aspects.

-

Make sure specialists are aligned with team’s objectives. The general outcome will be insufficient if only the specialist’s part is taken care of.

-

Make clear every specialist can be a generalist at some level. If there’s work to do, it is team’s responsibility.

-

Make people aware of their main tasks and responsibilities.

-

Foster collaboration and learning. Let people experiment different roles.

-

Consider people’s preferences. It is a bad situation having a necessary skill and no one willing to do the related work.

-

Inspect and adapt.